What is Budo Today?

Budo, the ‘Martial Way’ or ‘Military Path’ is typically related to Japanese martial arts such as Aikido, Karate-do, Judo, Kendo, and a number of others, but today the concept of Budo goes well beyond Japanese martial arts.

The term Budo is of relatively recent origin. Some even describe it as the Modern Military Way (Gendai Budo) to differentiate it from older forms of military arts (Old Form Military Arts – Koryu Bujutsu). We like to differentiate into ‘this’ or ‘that.’ There are wide paths, narrow paths, steep and rocky paths, career paths, and paths of least resistance. Paths come in many flavours. Today Budo has evolved to encompass both old and new thinking—it is an inclusive concept.

Budo today includes the older Bujutsu—a deep, multi-dimensional, and a broad subject to study. On top of that base, Budo becomes more than the mere application of military principles on the battlefield. It is a path that has as its end goal a well-balanced and self-fulfilled person. Studying Budo expands horizons physically, mentally, and in other disciplines such as art, music, science, philosophy and psychology; and if you want, it opens up a spiritual avenue to ponder.

Budo can apply to all martial traditions—Budo transcends one culture. Budo concepts cut across physical, mental, and spiritual boundaries. There are many tangible aspects of Budo and yet the real heart of Budo is intangible.

The unique Japanese flavor of Budo came from systematic study of martial arts endemic to that region of the world, but many concepts derived from this path have also been discovered by other cultures and continue to be used in current military science.

Budo Has Evolved

Just like Einstein who generalized Maxwell’s equations to a higher dimension to give us a new era of physics, principles of military science have been generalized on a number of levels and have evolved to give us Budo.

Just like Einstein who generalized Maxwell’s equations to a higher dimension to give us a new era of physics, principles of military science have been generalized on a number of levels and have evolved to give us Budo.

Budo as we know it today evolved from something quite different. Warfare is very old. Weapons, fighting techniques and strategies that worked became codified and relied upon for both offensive and defensive roles on both micro and macro scales; rulers fought for control of empires, and the common man protected his life and property.

Bujutsu: The application of technique—first appeared out of necessity. The ability to fight and the techniques that evolved were based on the pragmatic realities of survival. During these early eras, the military arts were studied with the sole purpose of destroying the enemy. Bujutsu is the application of military science and art to defending and attacking an opponent—Bujutsu is the pragmatic application of violence.

Bujutsu: The application of technique—first appeared out of necessity. The ability to fight and the techniques that evolved were based on the pragmatic realities of survival. During these early eras, the military arts were studied with the sole purpose of destroying the enemy. Bujutsu is the application of military science and art to defending and attacking an opponent—Bujutsu is the pragmatic application of violence.

Power was consolidated (in Japan this happened after the battle of Sekigahara 1600 A.D.) by Tokugawa Ieyasu as Shogun who founded the peaceful Tokugawa era. This parallel can be seen in many cultures, the warrior class began to pursue interest in other aspects of military thought to fill a void and justify its own existence during peace times.

Bushido: The ruling Tokugawa Shoguns also needed to control the military class and gave them an outlet for their energy by educating them. This was a code of conduct expected of a warrior stressing the concept of never pausing to consider the nature, significance, or effects of a superior’s command. The concept today has been romanticized to the extent that many do not distinguish it from Budo.

Bushido: The ruling Tokugawa Shoguns also needed to control the military class and gave them an outlet for their energy by educating them. This was a code of conduct expected of a warrior stressing the concept of never pausing to consider the nature, significance, or effects of a superior’s command. The concept today has been romanticized to the extent that many do not distinguish it from Budo.

Bushido was standardized, strictly adhered to, and formulated by those in authority to maintain control. Those who stressed the role of Bushido in reality espoused the role of the soldier, a blind obedience to orders, and not that of a warrior—someone who made up his own determination of whether to act or not. Bushido still is and has in the past been prone to fanaticism. During World War II, Bushido was used to create national fervor and military fanaticism that kept some Japanese hiding in jungles long after the conflict was over.

The ideals of Bushido, however, do have a place in our study of Budo. It is through Bushido’s sometimes harsh self-discipline that the realizations of Budo bear fruit. This is a seeming paradox. To gain freedom (in technique) you must enslave yourself to rigid discipline (training). Like a concert pianist, the Budoka must practice with dedication to enjoy the freedom and fluidity needed in both combat and music.

Despite its potential for misuse and fanaticism, major tenets of Bushido include what are known as the seven virtues:

• Rectitude

• Courage

• Benevolence

• Respect

• Honesty

• Honor

• Loyalty

These attributes are worthy of any Budoka. Today, Bushido alone is considered an incomplete way to achieve self-realization, but the discipline and training demanded by Bushido puts one into position to have a better understanding of Budo.

Budo: The term Do comes from Buddhist, Confucian, and Taoist (Tao is the Chinese equivalent of Japanese Do [Way]) philosophies. All suggest implicitly or explicitly that the pursuit of any worthy endeavor leads to spiritual liberation.

The pursuit can be anything: dancing, garden designing, tea ceremony, swordsmanship, etc. Once something is taken up and becomes a serious undertaking, it is called Do. In the case of Budo, the serious undertaking is the study of the Military Way.

Dreager’s Classical Budo (1973), an excellent reference to the historical origins of Budo, states:

“The creation of the classical Budo was indicated by the nominal change of the ideogram for Jutsu, ‘art,’ in the word ‘Bujutsu to Do, ‘way.’ This change heralded men’s desire to cultivate an awareness of their spiritual nature through the exercise of disciplines that would bring them to a state of self-realization. It is this goal that underlies the major difference between a classical martial discipline labeled ‘Jutsu and one termed ‘Do.’”

After examining Bujutsu, Bushido and Budo, we can see that the first two are subsets of the last—Budo has evolved to include the former.

We love the technical art of Bujutsu, finding better and more efficient ways of improving our technique. We understand the dedication and commitment required to become proficient, and have to overcome our fear through the discipline of Bushido. Budo allows us to find and understand, in a deeper sense, our relationship with our path in life. Budo is a ‘Way’ of life.

Budo Today

Today’s concept of Budo evolved in part from precursors such as Bujutsu and Bushido. Budo however, is not static, but rather dynamic, and constantly evolves. Kata change as each generation learns them. In some paths, the knowledge is enhanced, in others it is degraded. On top of all this, your understanding of Budo changes as you travel on your martial journey.

So how do you find the path that is right for you?

There are some guiding principles that can help you answer this.

Respecting the Past

Consider tradition with some respect for the hard lessons learned by actual combat. The past offers clues to your study to help you determine if you are on the right path.

Does the path you follow respect the study of solid Bujutsu?

As an example, modern sport while very important is still a sport. Too much focus on sport only narrows your path. While this may be an important aspect for you at certain times in your journey, there are other areas to study as well. Don’t get me wrong here. Sport is critical for developing many positive attributes in youth and elite athletes. My point here is are you learning combat or sparring? And what do you want to learn?

Does your Kata have depth?

Is there history in your Kata that gives you room to study. Make sure you are studying something that has not been distorted or creatively made up with no meaning. Dig into your Kata, its history, origin, geography, its variations among different styles of martial art. Assess your Kata critically.

Does the path you are following demand discipline and study?

Is your dojo a social place or a place for disciplined training? It should be both, in a balance that fosters personal improvement. If too skewed one way or another, why? What effect will this have on your personal development?

Value pragmatic and well-executed Bujutsu. Value the discipline and commitment it takes to do it well. Improve on it when possible without changing it into an esoteric art that has little real meaning.

Understanding the Present

It is easy to think of the enemy as being outside of yourself. Today’s Budo has given you an even more worthy opponent—Yourself—and if you dig deeper you realize that there is no enemy or self, there is just what some have called Tao.

Is your path only one dimensional?

Are you locked in only technical modes of thinking? Budo has a depth and breadth that can challenge anyone at multiple levels. Some specialize in unarmed or armed technical disciplines; others expand their study to calligraphy and the tea ceremony. Some can practice a lifetime and still feel like they haven’t penetrated very deep; others manage to pierce the very core of Budo. As you study you realize that Budo expands into other areas

To give you some perspective, there is a saying “Ken Zen Ichi Ryo,” which means “the sword and Zen are the same”—that through the study of the sword (Ken) one can achieve the same level of enlightenment as the study of Zen. This statement indicates that there are many dimensions that can be considered and explored. In this case, the link between Zen and Budo

Can you apply what you learn in different contexts?

Can you take fighting principles and apply them to other aspects of your life? Most of us live in relatively peaceful societies. Learning to apply martial concepts in different contexts makes us grow. For example, learning to apply pre-emptive, and reactive timing concepts (pre-emptive – Sen no Sen, reactive – Tai no Sen and Go no Sen) to other situations.

“A stitch in time saves nine” is really using a pre-emptive (Sen no Sen) approach to avoid a bigger tear in your clothes. This mundane example if considered carefully should give you many ways to lever this principle in many more interesting and complex ways.

Does you path make you a better person?

Are you focused only on winning by beating another person at his expense?—a zero sum game—or are you winning by creating a partner in the Dojo that can help you learn? What is winning?

Careful what you think here, you can have a tactical victory and a strategic loss at the same time. It all depends on what you set out to achieve. For example if my goal is to protect my family from an assault by two opponents, you can completely kill one (a decisive tactical victory) while letting the other assault your family (a strategic loss). Considering subjects such as what winning is can’t help but make you grow. I’ve only used the concept of winning here as an illustration.

Thinking about these things allows you to utilize these concepts in the boardroom and family life. Sometimes letting student throw you or your young son beat you at something is the surest way to create confidence and desire to learn, a strategy build on success not failure.

The Future of Budo

I have no idea what the future of Budo will be like. My own thinking is that Budo is a subset of Strategy (Heiho) and that is the avenue I am pursuing. Others will no doubt have other avenues to explore. Most importantly, I think the ideal of Budo—that of becoming a better person—involves a well rounded approach to the multiple facets of Budo, and to minimize distortions caused by focusing too tightly on single facets (i.e. Bujutsu only, or sport only, or meditation only).

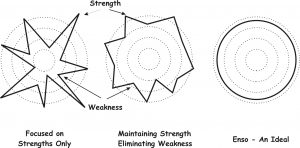

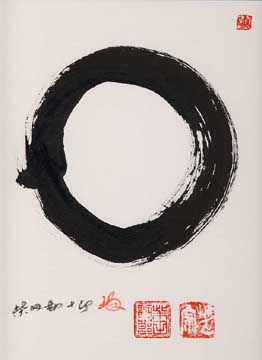

I’ll end this article using the concept of the circle or Roundness (Enso) found in many Zen paintings. If you focus only on a few strengths (left figure shown below), when you face your opponent, he will always attempt to evade your strengths and target your weakness. If you concentrate on building on your weaknesses to become less “pointy” as in the second figure, there will be much less for the opponent to exploit.

I’ll end this article using the concept of the circle or Roundness (Enso) found in many Zen paintings. If you focus only on a few strengths (left figure shown below), when you face your opponent, he will always attempt to evade your strengths and target your weakness. If you concentrate on building on your weaknesses to become less “pointy” as in the second figure, there will be much less for the opponent to exploit.

The Zen ideal of Enso symbolizes lacking nothing and nothing in excess—when the mind is free to let the body and spirit create whatever is needed under the circumstances you find yourself in. This ideal of a “well rounded” person that exposes little for the opponent to avoid or exploit is also the ideal of Budo.

Budo takes the points of Bujutsu, Bushido, Training, Mental Status, Psychology, etc. and rounds them into an ideal that we all strive for.

by Rick Rowell

http://budotheory.ca/blog/2016/12/30/budo-today/